Screwworm Eradication Program and History

Bottom line, the screwworm eradication program has been nothing short of a huge success story which for all practical purposes enabled the ranching community to eventually push the screwworm from their mind.

A very interesting article about the history of the screwworm eradication program, the current situation, and the efforts being made. I think any rancher would be interested in the information in this article.

NOTE: this article was originally published to LivestockWeekly.com on May 7, 2025. It was written by Colleen Schreiber.

Ask any seasoned rancher past the age of 70 and they will likely say that one of the best things the ranching community ever did to help itself was the screwworm eradication program.

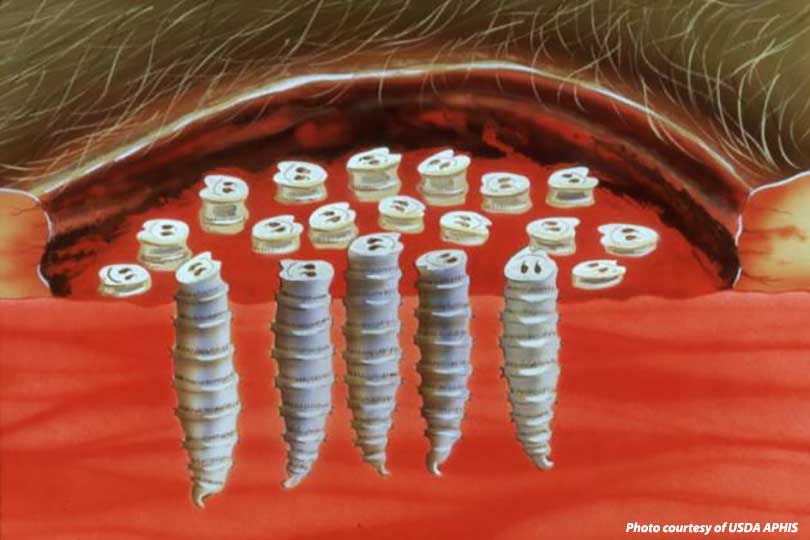

Now two, perhaps three, generations removed those who are ranching or managing wildlife operations likely have little to no clue what a screwworm is. They certainly do not know what it was like to battle them day in and day out through three seasons of the year or depending on the weather in some cases year-round, especially for those in South Texas. They may have heard old stories about those days, but few have experienced first-hand the daily checking for wormies, particularly during calving or lambing and shearing and branding seasons, and the ritual of roping and doctoring them by literally digging out the burrowing flesh-eating maggots with a stick or one’s finger and then applying foul-smelling pastes to the wound.

These pastes and concoctions, dubbed by various names like Smear 62, Bone Oil and the like, were only treatments, not antidotes. They were tools used by ranchers to try and save as many of their livestock as they could. If not done, the livestock or any warm-blooded mammal for that matter, would eventually succumb to the maggots. It was arduous, labor-intensive work. Good cowboys and good horses were essential to get the job done.

The hope for an actual remedy came about in the 1950s when two U.S. Department of Agriculture entomologists at the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Kerrville came forward with the sterile screwworm fly treatment. In the 1930s, Edward F. Knipling began formulating this idea of controlling screwworm populations by disrupting their breeding cycle through the release of sterile male flies. He had observed the sexual aggressiveness of the male screwworm and because the female mates only once he thought his idea just might work.

Fellow entomologist Raymond C. Bushland bought into the idea and began work on the laboratory technique for rearing and mass-producing screwworms. He also had to come up with a way to artificially feed this mass population of sterile flies.

The long and the short is, these two men developed the scientific technique that made the eradication of the screwworm a possibility. The ranching community then essentially made it a reality through private donations coupled with some government funding. The money was used to build the necessary fly production plants as it was understood early on that a lot of sterile flies were needed if this devastating pest was going to be conquered.

The idea of sterilizing male flies through radiation to then release them to breed with wild fertile females certainly seemed far-fetched to many, but forward-thinking ranchers understood that they needed to be open minded and give the concept a try. Thus, in 1958, USDA adopted the sterile insect technique.

The U.S. released the first sterile flies in Florida, starting in Orlando early that year and then in July in Sebring with a second plant producing and releasing 50 million flies weekly.

A Livestock Weekly article dated July 10 of that year stated that the “fly factory” at Sebring, where operations were geared to the Florida strain of the fly, housed six Cobalt-60 irradiation units thanks to the help of the Atomic Energy Commission. The other equipment included refrigeration storage for 83,000 pounds of meat and 4000 gallons of blood used to grow larvae.

The article went on to state that sterilized flies were transported in air-conditioned vehicles to airport distribution centers. Cardboard boxes of sterile flies designed to open on their own were then dropped by air over infested areas at a rate of 100,000 cartons per week. Each carton contained 500 flies, about half being sterilized males, resulting in 200 to 300 sterilized males per square mile. The number released was dependent upon the number of screwworm flies reported in the area by ground survey crews.

Used essentially as a proving ground, the Florida program was indeed very successful. Thus, work to establish a program in Texas began in earnest.

From the get-go, Texas ranchmen understood the urgency. While the plant at Kerrville, where Kipling and Bushland invented the technique, had the capability of producing the sterile flies, it was not at the volume needed as eradication of the screwworm in Texas was the goal.

Specifically, they recognized the need for their own production facility. They also recognized that it would likely mean years of waiting on the federal government to act particularly when it came to the funding piece. Thus, a group of visionary ranchers came together to form the Southwest Animal Health Research Foundation (SWARF), a private non-profit, supported and pushed along by men like then Governor Dolph Brisco, Charlie Scruggs and many others. Organizers of SWARF solicited the ranching community who gave from their pockets a large part of the money needed to build a plant.

Located on the southern Texas border at Moore Field on the old Air Force base at Mission, the plant was finished ahead of the anticipated timeline and the first sterile flies were released from that plant in early July 1962. By the middle part of the decade the screwworm was eradicated from Texas and in 1966 the U.S. was officially declared screwworm free.

That’s not to say there were not outbreaks, because there were the worst being in 1972 when 90,000 cases were reported. The outbreak was stomped back down in large part because the sterile fly plant in Mission was still functioning.

In fact, the work never stopped. Eradicating them from the U.S. and maintaining a 200-mile-wide barrier into Mexico was simply the starting point. Recognizing the need to push the pest as far south as possible, U.S. officials began encouraging Mexico to get serious about their own eradication effort.

The U.S. was willing to help because obviously it was in their best interest. Thus, in June 1965 it was reported in Livestock Weekly that a U.S. delegation met with Mexican officials to develop an international program. However, it wasn’t until 1972 that a final agreement was signed.

In 1976, the U.S. helped Mexico build a plant in Chiapas with a production capacity of 300 million sterile flies per week. Now equipped with 500 million sterile flies, 200 million from the Mission plant, from 1972 through the early 1980s, the screwworm barrier was pushed further and further south in Mexico.

By 1991, the screwworm was eradicated from Mexico and little by little through a concentrated effort the pest was pushed still further south beyond Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and on into Panama, to eventually reach the end goal, the establishment of a buffer zone at the Darien Gap between Columbia and Panama. That ultimately took until about 2000.

To aid in that process, in 1994, the Panama - United States Commission for the Eradication and Prevention of Screwworm (COPEG) was established. Governed by a commission of government employees, four from the U.S. and four from Panama, COPEG’s mission was to reach the end goal that being the Darien Gap, and then maintain the blockade, so to speak.

With that in mind, COPEG built a new sterile fly production plant which came online in 1996 in Pacora, Panama. The Mexico plant was closed in 2012, and today the COPEG plant stands as the sole remaining sterile screwworm fly production plant in the world with 90 percent of its funding then and still today coming from the U.S.

For the last nearly 30 years when there was a screwworm incident, COPEG’s army of inspectors would ride motorbikes, horses or travel via boats, whatever it took to respond, to treat the infected animal or animals. The coordinates of the infection site were given to the proper authorities at COPEG, and that area was then bombarded with sterile flies until the problem was rectified.

Bottom line, the screwworm eradication program has been nothing short of a huge success story which for all practical purposes enabled the ranching community to eventually push the screwworm from their mind. The long days of riding and doctoring wormies became something of the past, something that the old heads typically only relived through stories told to curious young reporters.

Unfortunately, now a reinvasion of this devastating pest, well beyond the Darien Gap and up into southern Mexico, is beginning to raise alarm bells in the U.S. ranching community. Those alarm bells began sounding last August when a group of four ranchmen, graduates and associates of the TCU Ranch Management program, traveled to Panama to teach a ranch short course at the university in Panama City. These individuals have been traveling to Panama a couple of times a year for several years now and over time have developed a working relationship with the ranching community. One of those men helped negotiate and draft the legal documents for COPEG.

On their trip to Panama in August 2024, the Texas group was startled to learn from this individual that there were now screwworm cases in Honduras. It was the first they’d heard of it because in truth the cases weren’t being reported or at least the news of these cases wasn’t being reported.

When the group returned stateside, Wayne Cockrell, who currently serves as the chairman of Texas & Southwestern Cattle Raisers’ Association cattle health and wellbeing committee and San Angelo veterinarian Chris Womack, also on the committee, immediately began raising the issue with federal and state animal health officials as well as their respective associations to find out what was going on. They not only voiced their concerns through the proper channels, but they also began getting the word out to the ranching community about the screwworm threat and the very real possibility that it could return to North America.

A few short months later, in November, the big bombshell dropped when Cockrell received correspondence from a Panamanian contact saying that the first screwworm case had just been reported in southern Mexico. While certainly a shock, Cockrell says it was not unexpected.

And it’s only gotten worse. As of May 22, there were 968 cases in Mexico. That makes it abundantly clear that not only has the screwworm infestation passed through Honduras, but it is making bigger and bigger inroads in southern Mexico.

And while the message is beginning to get to the ranching community in the U.S. that this is a very real threat, in the latter part of 2024 it simply did not seem that it was being taken seriously enough within USDA. Granted, USDA had and continues to have a lot on its plate with issues of foreign animal disease, namely avian influenza, but when questions were asked by concerned ranchers, insufficient answers were given, Cockrell said.

Thus, in April when the group from Texas was preparing to travel again to do their teaching seminar in Panama, they decided to see if there might be a possibility to visit the COPEG facility themselves to see what they could learn firsthand about the screwworm situation.

First and foremost, they wanted to know how control was lost. How was it that the screwworm was now back in southern Mexico and likely headed north? Second, they wanted to know what could be done to fix the problem.

The Texas delegation was openly received at the plant, and given hours of presentations on the operations and an in-depth tour of the entire facility including the production plant itself. They were extremely impressed not only with the facility but its dedicated personnel.

As for the why of how control was lost, what they learned was that it all began with the COVID pandemic. Just like in the U.S., just like all around the world, the day-to-day process of life, of going to work to do a job, essentially changed. The personnel in the field whose job it was to inspect the transit through Panama, the trucks and vehicles carrying livestock, were forced to stay home. There were also all kinds of other supply chain issues within the plant.

“Flies have to be released seven days a week, 365 days a year,” Cockrell stresses. “With COVID, missing one day, having infrastructure malfunctions, dirt bikes breaking down and no way to get the parts needed … that’s how COVID had an impact.”

They were told things like a three-minute interruption of power at the plant meant the loss of 15 million flies all because of a temperature change.

The second significant contributor was the open border policy of the Biden administration. The uncontrolled migration of people and animals from South America through the Darien Gap, through Panama into Central America essentially enabled the transit of the screwworm fly. Bottom line, surveillance was lacking.

Another potential contributing factor plant officials believe has been a change in the length of the screwworm life cycle from 21 days to now about 19 possibly even 18 days. A warmer climate pattern is thought to be a factor, but the long and the short is a two or three-day difference in that life cycle can be hugely significant. It comes down to inspection protocols and possibly the need to change those as well.

They also learned that just like in the U.S., and even Mexico, there is a generational loss of knowledge, even generational ignorance, as to just how serious the screwworm problem could become again if left unchecked.

And just like in the U.S. still another contributing factor is the profound change in land ownership. Absentee ownership is now the norm even in Central America. Cockrell says he’s been in Panama City on Saturday mornings when there is a line of Toyota pickups pointed in every which direction out of the city headed likely to their little ranch getaway in the country not unlike in the large U.S. metropolitan areas. People are no longer living fulltime on the land and that makes a huge difference in terms of management expertise and knowledge in general, Cockrell points out.

Not only has ownership changed but so too has the land as the Darien region between Panama and Columbia over the last 20 years has been transformed from a forest of trees to open grasslands.

“They’ve planted all these Brazilian grasses and now it’s become the flint hills of Kansas for yearlings,” Cockrell insists. “They’re weaning bull calves and sending them there for a year and then those two-year-old bull calves are loaded on bobtail trucks headed north.”

The COPEG officials also acknowledged that there was a lack of cooperation, collaboration and communication between the government agencies, the producers, the trade organizations and veterinarians about how important it was to report and treat but particularly to go through the inspection process before the cattle are shipped. Not doing that one simple step meant that the problem was carried from the southeast side of the Panama Canal to the northern side.

“A carbon copy of all these issues happened in every country all the way to Mexico,” says Chris Womack, DVM.

The good news is that the Texans also learned on their trip in April that COPEG is doing everything it can to get the problem rectified. For starters, they most definitely learned from the COVID experience. Today the plant has eight months’ worth of backups of everything from motorbike parts to 10 million gallons of stored water capacity as well as more backup generators, basically everything they need to run the plant should a supply chain disruption occur or if God-forbid another pandemic of some sort were to occur.

Most notably, since October the 600 employees who man the plant, have taken fly production from 25 million per week to 100 million-plus.

“They’re operating a 30-year-old plant at redline capacity,” says Cockrell.

The process developed and perfected in the 1950s and 60s is essentially the same still today. A Livestock Weekly article from February 22, 1962, described the process in some detail noting that radiation is done in the pupae stage where some 18,000-20,000 are put in a six by 18-inch-tall tube and then lowered into a cobalt chamber for 13 minutes.

After being irradiated the pupae were tested for sterilization and once approved a couple hundred pupae were packaged and stored in small boxes until hatched. It is these small cardboard boxes that were then tossed out from the air or an automobile window at a rate of one box per square mile.

Still today at the COPEG plant, fly production centers around the brood population of flies which currently stands at 2.5 million. It is from this brood population that the flies are produced, and a portion of the males ultimately are irradiated.

There is a constant evaluating and testing of the virality and aggressiveness of these brood flies adding in hybrid vigor from flies collected in the wild when needed. The 18-to-21-day life cycle of the screwworm fly is mimicked in the laboratory and monitored like clockwork essentially 24/7.

While scientists are continually looking for new technologies to improve and streamline the process, mass production of sterile flies is the sole answer to keeping the screwworm eradicated even with the small differences in the process that have been made. For example, no longer is raw meat used to feed the larvae. Today it’s synthetic flesh. However, that does not mean the intricacies of the process, namely knowing what it takes to get these flies to consume the synthetic flesh, is any less critical. For example, the pH and the temperature must be precise.

“You can’t fool these flies,” says Cockrell. “It must appear to be healthy, living flesh, so the quality control at the plant is critical and phenomenally well-done.”

Another small change in the storage and distribution of the flies has been made. For example, the pupae are no longer stored in cardboard boxes but rather in small cylinder type containers.

The specialized boxes/containers are loaded on the plane, then opened in flight and the flies are released crop duster fashion, says Womack. Within 36 to 48 hours, the males, again bred for virility and aggressiveness, began seeking a female to mate.

The female then lays her eggs in a wound or orifice of any warm-blooded mammal and within hours the larvae begin feeding on the flesh. After seven days, the pupae drop off the host and burrow into the ground where they spend the next seven days before hatching into flies whereby the process begins anew.

Officially, scientists say the flies can travel 12 miles, but there are known instances where they’ve traveled hundreds of miles largely during a tropical depression, hurricane or via a warm-blooded host being transported by truck, train, plane even by foot.

Interestingly, because the screwworm population is thankfully still very low, ARS scientists are now trying to develop new pheromone attractants to attract the flies to the fly traps for testing and further evaluations. They’re also working on some potential gene editing to induce brood females to lay more male eggs thereby increasing the production efficiency at the COPEG plant. Plus, they’re looking at changing the type of radiation used from the cobalt 60 generators to electron pulse type generators to try and make a new sterile fly facility cheaper to construct and with fewer regulatory requirements.

There is also some work being done in South America that suggests that treating an animal with an injection of Doramectin can provide protection from the larvae for 21 days.

Regardless, while all these technologies are certainly important experts say bottom line it still comes down to ramping fly production.

“The flies can do the work if they can overwhelm the wild fly population,” says Cockrell.

That is why in the last six or so months the Panama plant has increased production from 25 million to 100 million flies per week. The need is that great and still that is not near enough. All fly production is now centered in southern Mexico at a rate of 3000 sterile flies per square mile.

At least that’s what was intended. In reality, what they also learned on their visit to COPEG was that the Mexican government and other entities within Mexico is now where their biggest problems lay. Specifically, Mexico is throwing up all sorts of barriers, all sorts of obstructions, everything from allowing planes to only fly on certain days and planes having to stop on the southern Mexican border for customs inspection and being charged exorbitant fees and ultimately limiting the number of planes dispersing flies from six down to one. Additionally, USDA personnel had to be under armed guard and military escort when going into Mexico to perform inspections.

Since the outbreak in Mexico, in all only 12 planes have been allowed to drop flies. The other 20 planes that are available have continued to operate out of Honduras.

It got so bad that a week or so ago, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins sent a terse letter to her counterpart in Mexico demanding that Mexico do better, that the issue at hand was a grave one and if they did not do their part that the U.S. would close the border to imports.

The letter got a reaction. Mexico has since promised to open the airspace and allow the mobile distribution facilities and planes to operate freely as needed. Additionally, it’s been reported that as of April 30, the General Director of Animal Health of Senasica, MVZ Juan Gay Gutierrez, has resigned.

Industry has voiced their thanks loud and clear to Secretary Rollins for her efforts of holding the Mexican government’s feet to the fire. Cockrell says if Mexico does not hold true to their commitment U.S. producers stand behind the secretary in her pledge to shut the border.

“If we don’t stop it now and the outbreak moves into the greater area where the landmass of Mexico gets broader, where there are more livestock and more wildlife it will become all the harder to control,” Cockrell stresses. “Right now, the line of control is only 700 miles from Brownsville.”

The director of COPEG was hopeful that all the mobile dispersal facilities would be shifted from Honduras to Mexico by May 3 and running at 100 percent the second week of May.

Looking back Cockrell admits that there were things that he too wishes he would have done differently. He recalls meeting a group of Panamanians for the first time in 2012. They came not only to visit Texas ranches but to lobby state and federal animal health groups and other government officials from closing the sterile fly plant in Mexico. They lobbied because they recognized that fly production at the COPEG plant was their only backup defense should the screwworm ever break out of the quarantine barrier again. Unfortunately, their pleas fell on deaf ears. Cockrell blames himself as much as anyone.

“We should have been listening; we should have been doing our own lobbying,” Cockrell admits. “But it goes back to that generational loss of knowledge. We simply didn’t understand the value of that plant.”

Now 13 years later that decision, that lack of concern, perhaps even complacency is haunting the U.S. cattle industry. Now getting the word out, telling the story of what’s happening in Panama and to the north, scaring officials into action, educating the general populous but particularly the younger generations of landowners, managers and the like has become Cockrell’s and Womack’s primary focus. It must start there, says Womack.

If there is a silver lining, it is that ARS is now able to identify the genetics of the wild screwworm flies confirming that the genetics of the screwworm found in the first infestations in Honduras and even now in Mexico are a strain of Caribbean genetics, be it from Cuba or the Dominican Republic.

Still, even if Mexico cooperates and COPEG stops it at the current line of control in Mexico, the U.S. still faces the threat of illegal movement of cattle, people, and the fly’s instinct to move North likely for the next 20 years until the line of control is pushed back down to the Darien Gap, says Cockrell. As he reiterates, there are simply not enough sterile flies to move it back down there currently.

That’s why Cockrell, Womack, and a host of others have already begun the lobbying effort to build a new sterile fly plant in Texas and Secretary Rollins has also pledged her support for the construction of such a facility.

There have been all kinds of estimates and timelines floated. They’ve heard that it would take two to three years to build a plant at an estimated cost of $350 million. Whether that’s factual remains to be seen. Regardless of the cost, the two ranchmen stress that it must be controlled by the U.S.

“We can no longer give away these facilities that were paid for with our tax dollars,” says Cockrell.

Womack agrees.

“Our parents and grandparents paid for the original plants. Private individuals put up a third of the money, $3 million of the total required to build the facility in Mission,” Womack reminds. “They didn’t wait on the federal or the state government to do it. It was an amazing effort, and if we don’t learn from that lesson then shame on us. If we don't step up and at least educate the next generations about the importance of this, and if we don't increase the research efforts and the funding for the research then shame on us because we’re dishonoring the efforts of our predecessors. That's a bitter, bitter pill to swallow.”

He also points out that it’s not just the livestock industry that will suffer the economic consequences. Allowing the screwworm to reinfest North America will have a profound impact on the wildlife and hunting industries which brings in an estimated $9 billion annually to the U.S. alone.

“Education is paramount,” Womack reiterates. “If you’re lucky enough to have your grandparents, ask them about the screwworm. If nothing else Google it. Talk to your veterinarians, become aware, and become vigilant. Know what to look for.”

“Our predecessors had it worse for years and years, and they made something that seemed far-fetched at the time a reality,” Cockrell adds. “I hope that same attitude, that same get it done spirit is still in all the producers in Texas today. We must unite and push this screwworm problem back to the Darien Gap. As a Texan, I have faith that in the end, we will step up.”

Finally, both men stress that while there are complicating factors at hand the age-old principle is still the same, that it is the sterile flies that are the workhorse and more workhorses are needed.